Through the Contact Group begins Russia’s re-engagement in Bosnia in the early 1994 (Secrieru, 2019). For this task, Russia appointed promising Russian diplomat Vitaly Churkin who served as a Deputy Foreign Minister and the Special Representative of the President of the Russian Federation to the talks on Former Yugoslavia. General perception of Russia that it is sympathetic to Serb goals, which partly attributed to identity linkages but also and perhaps more importantly by strategic considerations and general suspicion of the western and NATO expansion.

Russia’s weakness and insignificance persisted during the immediate period after the war and the implementation of GFAP (General Framework Agreement for Peace), or the Dayton Peace Agreement (DPA). Russia followed the overall western course that Bosnia was set on by an overwhelming international apparatus on the ground and the western dominance. Russia participated in the work of the Peace Implementation Council (PIC), an advisory body to the High Representative for BiH. Russia was not an opposition to BiH ‘s Euro-Atlantic integration at least until 2002. Putin’s rise to power hallmarked the ascent of different kind of Russia and consequently Russian policies in Bosnia underwent a fundamental redress.

Coincidentally, the emergence of clearly defined Russian energy policies reinforced by identity-based linkages coincide with the beginnings of Russian quarrel with the West. Russia and West will collide head-on over the course of action in the PIC. Roughly at the same time, Russia privatizes the oil induytrs of Republika Srpska ( and the only such in Bosnia and Herzegovina) increasing and strengthening its footprint. Milorad Dodik, a primary political figure in the RS, undergoes radical transformation from a progressive politician favoured by the West to nationalist and a staunch opponent of the OHR and the West. Dodik’s ever louder call for a redress of the country, his outspoken irredentism, and unequivocal challenge to the Western dominance result with straightening of his linkages with the Russian Federation.

Overall deterioration of relations between Russia and the West was by no means endemic to Bosnia. Russia’s resurgence was much broader in scope and its ensuing conflict with the West found its materialization in Bosnia as well. In Bosnia, the conflict and increasingly hostile relations were augmented by the very nature of country’s post-war setup. DAP gives to the international actors in Bosnia relatively strong leverage by which they can influence processes in the country. System was gradually upgraded to allow for ever stronger role for the international faced with obstructions during early post conflict phase. Thus, the strategic vision pursued by local actors in BiH developed under relatively strong western influence. In retrospective, and from this fact alone, the conflict seems to have been inevitable.

Second important aspect is the nature of conflict in former Yugoslavia where Serbia and its kin looked up to Soviet Union and later Russia for support, while their opponents sought allies in the West, be it Europe or the US. This narrative is particularly important for largely misplaced perception of the Russian footprint in Bosnia and consequently its disproportional impact on domestic affairs in Bosnia.

Thirdly, the identity character of conflict in Balkans enables Russia the easier entry. Invoking the Orthodox element of identity relations resonates particularly well with ethnic Serbs populations in the region, and Russian influence thrives relatively well on it.

Fourthly, Russia, being itself an unconsolidated democracy does not pay very much attention to the quality of democracy in the region. Unlike western actors whose important goal was democratic consolidation of the region (post-war Bosnia is in this sense an excellent example with a number of its institutions and procedures designed in the likes of similar advanced models from the western liberal world), Russia mostly turns the blind eye to corruptive practices of current political elites or their proxies in the region who are actively undermining democratic institutions and procedures.

Fially, while all te above mentioned elements allow for a stronger Russian footprint in Bosnia and the region, Russian continues to observe the region in general, and Bosnia in particular, through the lenses to geopolitics, energy interests, and the ongoing conflict with the West.

Sliding into conflict and emergence of alliance

Series of events from the period of 2006-2007 set West on the collision course with Russia. Probably the most significant was the unilateral declaration of independence of Kosovo followed by the recognition by major Western countries. While the event in itself in a way represents a continuation of trends from mid- to late 1990s. Russia felt once again completely side-lined in the process but this time, it was not the same Russia. Western misapprehension of Russia’s increasingly assertive position will cause deep problems the region and in Bosnia and Herzegovina. In the latter, the spat occurred over two issues, the police reform and the closure of the OHR (Huskić, 2020).

Police reform in BiH was actually not a new issue. It belonged to the larger segment of security sector reforms which started immediately in the aftermath of the war under the guidance of the UN International Police Task Force (UNIPTF). All these reforms aimed to improve the substantive part of police work to put it in concordance with the requirements of modern liberal democratic order. Administrative and fragmentation and decentralisation of police forces was initially not the focus of activities. It was only at later stages and under the umbrella of the now EU-led police mission (since 2003) that these issues came to fore when the police reform requirements became part of EU Stabilisation and Association Process (SAP). Under the surface and largely unnoticed Bosnia was undergoing radical transformation of international presence during the first half of 2000s signified by a declining American presence and increased role for the EU. Moreover, the EU’s approach to Bosnia relied heavily on the positive momentum of reforms which were believed to be irreversible by now. Bosnian was thought to be on a stable path of transition from Dayton to Brussels phase. This meant a phase-out of international presence and activism and a transfer of ownership over processes to domestic actors. Final and most serious upset was the onset of a constitutional reform debate with not as strong US leadership and supported by European which culminated with its defeat by a two-vote margin in the BiH Parliament. Following this debacle, the US turns away from Bosnia and European inherit a constitutional reform process which is now understood not only as an exit strategy, but also as a final proof of maturity of domestic political elites. With constitutional reform, BiH politicians would finally assume responsibility for their affairs and be able to enter into negotiations proper with the EU. Russia was standing aside for the whole constitutional reforms process.

Police reform followed roughly the same trajectory as the constitutional reform debate, yet under European leadership and increasingly important role by played by Russia. Both initiatives were launched while the active and heavy western involvement in Bosnia was subsiding. Furthermore, the Police reform showed lack of clear incentives for domestic players and the effective leverage on the European side to broker an agreement in the absence of strong US pressure. Police reform debate fell victim to the changing political dynamics in the country achieving only partial success (Huskić, 2020).

Visible manifestation of differenced occurred at the Steering Board (SB) Meeting of the Peace Implementation Council (PIC) – body tasked with overseeing the implementation of the DPA – on 27 February 2007. Common practice after each PIC or PIC SB meeting was a joint communique outlining conclusions from the meeting and indicating the main course of actions or stance of the international community in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Those were perceived in public as a desired course of actions the international community demanded from the local actors. Previously backed by coercive actions of the HR those conclusions have meanwhile become a soft power mechanism that Bosnian authorities and political elites were supposed to follow. In February 2007 the SB could not agree on the text of joint communique for the first time since the end of the war. Russia lodged a dissenting opinion indicating a profound change of course driving a wedging in by then relatively unified (and western-dominated) international presence in Bosnia (PIC Steering Board Political Directors, 2007). The issue at stake was Dodik’s direct confrontation with the international community over the High Representative’s (HR) decision changing the procedures for the adoption of decisions in the Council of Ministers and the Parliamentary Assembly of BiH.

Russia’s political support coincides with obscure privatization of Republika Srpska oil sector by NeftegazInKor (НефтегазИнКор) , a daughter company of Russia’s state owned Zarubezhneft. in 2007. RS oil sector which consisted of oil Refinery Brod, Motor Oil Refinery Modriča and Petrol distribution stations was sold for 121 million € following Dodik’s government’s decision to privatise the oil industry under special condition by amending the Law on Privatisation and employing a direct agreement model, which meant circumventing transparent public procurement procedures. Privatisation contract was never publicly disclosed in its entirety and remains such to this day.

Parts of the deal that were disclosed show how disastrous the deal was for RS. RS took on itself to cover all outstanding debts of Oil industry amounting to 215 million KM, making a whole privatization deal only 15 million KM (roughly 7.5 million €). Process of privatisation damaged some 15.000 individual shareholders whose share values dropped incurring losses of almost 15 million KM. Meanwhile for the Oil industry of RS accumulated more than 700 million KM (~ 350 millon €) debt, while Brod Refinery stopped working since the accident in 2018.

Rise in Russian leverage in RS and Dodik’s increasingly defying stance can therefore be observed as part of the same process of convergence of Russian and Dodik’s anti-Western attitudes. Dodik, who was at the time only shyly experimenting with rejecting western-liberal values and course of action, saw the decline of western-dominated international presence and the emergence of Russia primarily as a setting against which he can solidify his position and establish himself as an indispensable element of Bosnia’s political landscape. Careful examination of relations between Russia and the RS (BiH) shows that Russia wield influence in BiH and via RS without investing much. Demand side, usually neglected in analyses, represents an important variable in this sense.

Russia and the West further diverged in Bosnia over the closure of the OHR. Closing the OHR as a symbol of international administration in the country was an ongoing process supported by Russia and Europeans in early 2000s. As mentioned earlier, the Europeans saw in it a signal that Bosnia is ready for self-government and politically mature, whereas Russia saw the establish effective control over processes in Bosnia by aligning with veto-wielding Republika Srpska political elites, who were across the board sympathetic to Russia. This would enable Russia to stall and possibly reverse the NATO expansion into region (BiH) and would be a useful leverage in talks with Europeans. Also, on the symbolic side, “getting rid of the body established by GFAP at the time when Russia was far too weak to engage fully in Bosnia, will become instrumental in reasserting Russian influence in the country” (Huskić, 2020). Deterioration of political situation and stalling of reforms prompted western countries to backpedal on their decision to close the OHR, opting in turn for a set of conditions to be fulfilled which would then allow for proper phase out of international presence. In 2008 they laid out a set of requirements to allow for the closure of the OHR contained in so called “5 + 2” agenda. Closure of the OHR will remain a primary objective of Russia’s BiH policy.

Meanwhile Russia begun contesting Bosnia’s NATO and more recently even EU integration. An overview of diplomatic activities related to Bosnia from publicly available Russian MFA records illustrate the change in approach. Until 2004 there were no official meetings between Russian and RS authorities. They begin and intensify in the period after 2006. First meeting with Milorad Dodik took place in January 2007 in Moscow, shortly before the controversial privatisation of RS Oil industry deal was closed.

Russia and BiH state, ethnic groups and regional (im)balance

Russian high-level officials were always visiting the state capital first, and the RS later. During last visit by FM Sergey Lavrov Russia broke with this practice meeting instead first with the RS authorities, which described the visit as the visit o RS. Later that evening Lavrov met with the leading Croat politician Dragan Čović, while the visit with state-level was foreseen for a day after. Two members of BiH tripartite Presidency, Bosniak and Croat cancelled their meeting with Lavrov citing as reason Russia’s open calls for the closure of the OHR and opposition to NATO path, though some observers, and even Lavrov himself, considered this to be an act “someone” suggested, hinting at western actors. Meeting with Daga Čović is particularly interesting in light of an ongoing and perennial constitutional reform debate. Russia, as mentioned above, is a status quo player in BiH. The country designed in such a way is unable to make any move internationally that would go contrary to Russian interests. Calls for reform of the constitution form the West (be it the US, EU, or CoE/ECtHR) go along the line of reducing the veto points and the dominance of ethnic groups in BiH. This is seen as detrimental to Serb and Croat elites’ interests who see maintenance of ethnic-based structure as their paramount objective. Two neighbouring countries (Serbia and Bosnia) are already inextricably part of the process, while Russia sees its interests served in siding with Serb and Croat political elites and ensuring that no progress can be made in either reforming the country against its wishes or bringing it closer to either NATO or EU.

Russia’s economic footprint

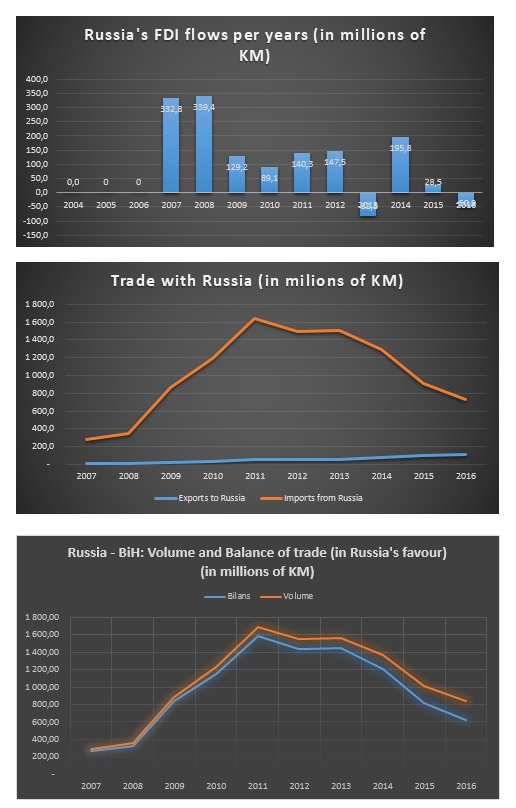

Despite general perception (as visible in the repeated polls by IRI) Russian economic footprint in Bosnia is relatively small. Russian investments in BiH are mostly found in the RS and they peaked in 2007 and 2008 with privatisation of the Oil industry of RS. This remains to this day the largest Russian investment in BiH. Worth noting is that despite Russia’s amost exclusive focus on the RS, it represents only 11% of total investments in the RS. In addition to Russian investments in energy sector via the acquisition of Volksbank by the Russian Sberbank Russia increased its footprint in the banking sector as well. Sberbank in BiH acquired in the process 30 branch offices, 1 090 offices, more than 100 000 individual clients and 420 employees.

Trade relations between two countries remains relatively small while exhibiting an increase in the volume from 2008 until 2011. After 2011 exports from Russia are steadily decreasing whereas Bosnia’s export to Russia remain low exhibiting very gradual growth which corresponds to the introduction of sanctions by the West to Russia for the annexation of Crimea. Bosnia did not join the sanctions and managed to capitalize on this by increasing its exports to Russia during this period. Over the course of several years, Bosnia increased its exports of mainly fruits and vegetables to Russia.

However, Bosnian economy has achieved relatively high level of convergence with EU which makes any fundamental shift highly unlikely. Russia, on the other side, does not seem particularly interested in increasing its economic leverage in Bosnia, partly because of Bosnia’s investment unattractiveness, and partly because their interests lie elsewhere.

What about BiH’s strategic orientation

Changes in Russia’s position towards the West led to gradual shift in their support to NATO and even the EU membership of Bosnia and Herzegovina. At the time of writing, Russia openly opposes Bosnia’s bid for NATO membership praising RS National Assembly’s Declaration on Military Neutrality. RS officials frequently tie their relationship with NATO to Serbia’s position in this sense. Russian officials are also advocating “alternatives” to the EU membership, for example in the form of stronger cooperation with Russia, Turkey and China (Vijesti.ba, 2014), even though none of these alternatives appears to serious.

Russia does not invest in media in BiH, opting instead of investing in Sputnik in Serbia as its mouthpiece which cover into Bosnia from there perpetuating Russian and Serbian interests (Vele, 2017). In terms of cultural cooperation with RS or Bosnia, Russia lags very much behind other states. Since 2012, Banja Luka Peoples’ and University Library hosts “Russian cultural centre Russian World” (Русский мир). Foundation Russian World was established by President Putin in 2007 with an aim to promote Russian culture and language in the world via Russian cultural centres Russian World. Foundations of Serb-Russian Shrine and spiritual-cultural centre in Banja Luka which, build in honour of Romanov family, were laid in 2018 during Lavrov’s visit to BiH and the RS. The land for the construction site was donated by Banja Luka tycoons close to Dodik and RS citizens will finance the construction. Whole above mentioned section clearly shows that Russian simply does not spend any significant resources in increasing and maintain its leverage in BiH via the RS.

Conclusion

Russia becomes relatively prominent stakeholder in Bosnia after 2006. And while Russian engagement with the region and BiH certainly predates this, the level of engagement and ability to influence processes is radically transformed during this period. Russia enters the stage shortly after Kosovo declares independence backed by some western countries and at the time of police reform debate in Bosnia. It breaks ranks with other countries in PIC siding instead with RS authorities and increasingly confrontational Milorad Dodik. At around the same time, Russia enters into energy sector in Bosnia, privatizing the Oil industry of RS in rather controversial and shady deal. Oil industry deal remains to this day the largest Russian investment in BiH and the RS. Until 2018, RS Oil industry now under an umbrella company Optima Group generated more than 2 billion KM (~1 billion €) of losses. Mismanagement of otherwise potent segment of economy begs questions whether the money is being drained out of company and whether political support for Dodik was paid with it. Simultaneously with privatization of Oil industry, contacts between Russian and RS politicians increase in frequency. However, Russia never shifts its focus entirely to RS at the expense of BiH, maintaining instead regular and permanent contacts with both. All Russian state officials during the observed period visited Sarajevo and in addition Banja Luka, breaing with this practice for the 25 anniversary of the signing of DPA. In terms of support, Russia appears mainly reactive echoing Dodik’s rhetoric when needed, which points to conclusion that Russia seeks ot maintain the current political setup and does not see Bosnia as an important part of its strategic and regional agenda. Nature of relations is such that Dodik wields his Russian legitimation freely and mostly for domestic political purposes in Bosnia and in Serbia, with tacit Russian approval. Russian policies in Bosnia on are aimed at closing the OHR and removing western international presence, which is what Dodik advocates too. Convergence of goals and agendas is in this sense fairly easily identifiable. Dodik met with Putin eight times since 2011, always for a rather short time and almost always on the margins of an event that Russian president attended. Relative insignificance of Russian economic footprint in RS and BiH in terms of trade, where Bosnia runs trade deficit, and somewhat better ranking in terms of FDI, is contrasted by the perception of Russian influence where Russia is frequently seen and perceived as a major political player in Bosnia. Bosnia’s broad consensus requirements and divergent ideas about country’s general course between the three dominant groups render the country unable to make foreign policy decisions which could be detrimental to Russian interests or agenda in the region and beyond. Russia therefore appears to be most rational actor of the four examined exhibiting almost exclusively instrumentalist logic behind it actions. Elements of identity-based logic serve in this case only as a useful tool and vehicle.

Adnan Huskić, Sarajevo School of Science and Technology